Willie Mays Aikens’ off-the-field story has been told before. A budding MLB superstar in his early 20s, his career would succumb to a 20-year prison sentence for crack cocaine charges. He’s admitted to living a past life where he smoked crack nearly every day and slept with prostitutes.

Understandably, people have overlooked the story of Aikens on the field, which is far less told and no less captivating. It is a story of how the game of baseball (and sports in general) can be a second home, a release – and in some cases – a redeemer.

It begins in Seneca, South Carolina, in a small neighborhood called Bruce Hill.

“I started playing baseball, football and basketball when I was six or seven,” recalls Aikens. “I just remember being really good at all of them. I made the varsity baseball team in 8th grade and my coach Willie McNeil took me under his wing. He told me I had the chance to be something special.”

Aikens was bigger and stronger than most of his classmates and while his size helped in sports, it also contributed to making him an easy target for teasing. “I had a speech impediment, so other kids used to make fun of me and since I was a big guy, they used to call me fatso.”

In addition to his personal struggles, he also had to deal with racial issues that were prevalent at the time. “I grew up in the south in the 50s and 60s and it wasn’t a very pleasant place because of the racial tension. I remember bathroom signs saying ‘blacks only’ or ‘whites only,’ water fountains for blacks, water fountains for whites, it really was pretty ridiculous. I remember in 1959 when they integrated the schools, that was crazy. I didn’t know what really was going on, I just accepted it.”

“My childhood certainly wasn’t anything to brag about,” Aikens recalls. “I grew up poor, grew up in a shack. We had outhouses as bathrooms and no running water inside the house until I was about 15 or 16. My mom was a street lady, I never had a chance to meet my real dad and my stepfather was an alcoholic that died when I was 14 years old.”

“But my playing sports outweighed everything.”

Aikens would eventually earn a football scholarship at South Carolina State University, where he also played baseball. During a summer ball game in Washington D.C. after his freshman year, Aikens met a gentleman named Walter Youse, who asked him to come to Baltimore to play for an amateur team over the summer. “The team was owned by a used car salesman and when Walter started naming off names like Reggie Jackson, Al Kaline and others that had played for the team and become major league players, I was sold.”

“Walter told me that if I came up he’d find a place for me to work and a place to stay,” Aikens remembers. “I got a job working as a laborer for a construction company that was building a JCPenney, and I stayed with a school teacher. On our off days, Walter would take me to Memorial Stadium, where I would catch batting practice for the Orioles and then they’d let me hit a little bit.”

“I was up there when my South Carolina State dropped its baseball program.”

The Next Chapter

Youse, who planned to pick Aikens in the upcoming (January) MLB Draft, advised him to return to South Carolina State for a semester, knowing that he would still be on scholarship for football. “I asked the [football] coaches if I could keep my scholarship for a semester and not play football, and they let me do it. They allowed me to come back to school.”

Aikens was watching the MLB Draft on January 5, 1975 when ironically enough, the San Diego Padres chose SCSU teammate Gene Richards (who would play eight MLB seasons and set a modern-day rookie record with 56 stolen bases in 1977) with the first overall selection. Aikens sat back and got comfortable; the Orioles had the 24th and final pick of the first round so he had some time to wait.

Or so he thought.

“The Angels had the second pick and they picked me! I'm like, ‘how did the Angels draft me? Walter was a scout for the Orioles!’ Well, about fifteen minutes later Walter called me and said 'I got ya! I quit the Orioles two weeks ago and went to the Angels.’ He came to South Carolina, I signed the contract and the rest is history.”

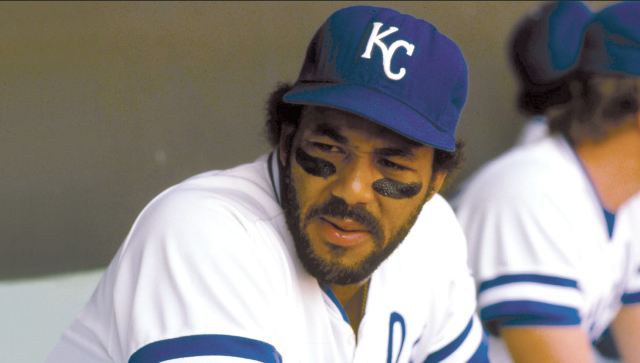

While it may have been cut short, that ‘history’ as it relates to Aikens’ playing days is truly impressive. In 1979, he led all MLB rookies in home runs, with 21. The following year he made an even bigger splash, helping the Kansas City Royals advance to the World Series. During the 1980 Fall Classic, Aikens became the first person in history to hit two home runs in two separate games during the World Series. He also drove in the winning run in game three. The Royals, who were the first American League expansion team to reach the World Series, would ultimately lose to the Phillies in six games.

Aikens batted better than .265 and hit 17 home runs in both 1981 and 1982 before the best year of his career in 1983, where he swatted 23 homers and hit .302. While it seemed like the beginning of an illustrious career, it was simply the beginning of the end. Towards the end of the ’83 season, Aikens and some other Royals pleaded guilty to attempting to buy cocaine and were sentenced to three months in prison. The year after, he was found guilty of selling crack cocaine to an undercover police officer and thanks to the brand-new mandatory minimum laws, he was sentenced to more than twenty years in prison.

In 1985, Willie Mays Aikens was behind bars. And the Kansas City Royals won the World Series.

Eventually the mandatory minimum laws were overturned (due to disparity in crack and powder cocaine cases) and Aikens was released after nearly 15 years. He chronicles those years in his book, Safe at Home, which award-winning freelancer Amy K. Nelson has called “as honest and transparent an account of an athlete's life that has ever been written.”

“The book was written because I was gone for a long period of time, fourteen years I was incarcerated,” Aikens recalls. “I had to deal with drug addiction and that mess, and I guess the book is kind of a guide to pull you out of those problems, to tell you that it's not the end of the world. It was a blessing for me and my family and I think for other people too. I also rededicated my life to God when I was incarcerated. Sharing my testimony of how good God is, I’ve had a lot of feedback from people who are in prison and their families, from people addicted to drugs and alcohol.”

Aikens also has the opportunity to share his story with current professional players, serving as the hitting coach for the rookie-level Arizona League Royals, a post he has held since 2011. His baseball mind is still as sharp as the sound of the crack of his bat.

“Coaching can be tough,” he admits. “I feel like I still have the mind of a Major Leaguer and I've been in rookie ball. I've had to learn how to deal with calming myself down and not overreacting sometimes. It's all about development.

“I think [rookie ball] is the most important level – it’s an introduction to professional baseball, to being away from home. What you learn in rookie ball, you can use for your whole career. Because of what I've gone through, I have the chance to be a mentor to these kids as far as living a life off the baseball field. Some of our guys have read my book and can't believe that I was in the big leagues and that I was also incarcerated

for 14 years. It's truly been a blessing to get the chance to work for a professional organization like the Royals. I am truly thankful to the Glass family, [general manager] Dayton Moore and the entire organization.”

In addition to his coaching, Aikens has also made a multitude of public appearances, speaking out against

drug abuse. “Each and every time I speak is a reminder I have to live life one day at a time because I don't ever want to go back to that life again.” 2015 makes it thirty years since Aikens played in his last MLB game, in 1985. Here’s hoping his next thirty years have the same result as his last big league at-bat – a home run.