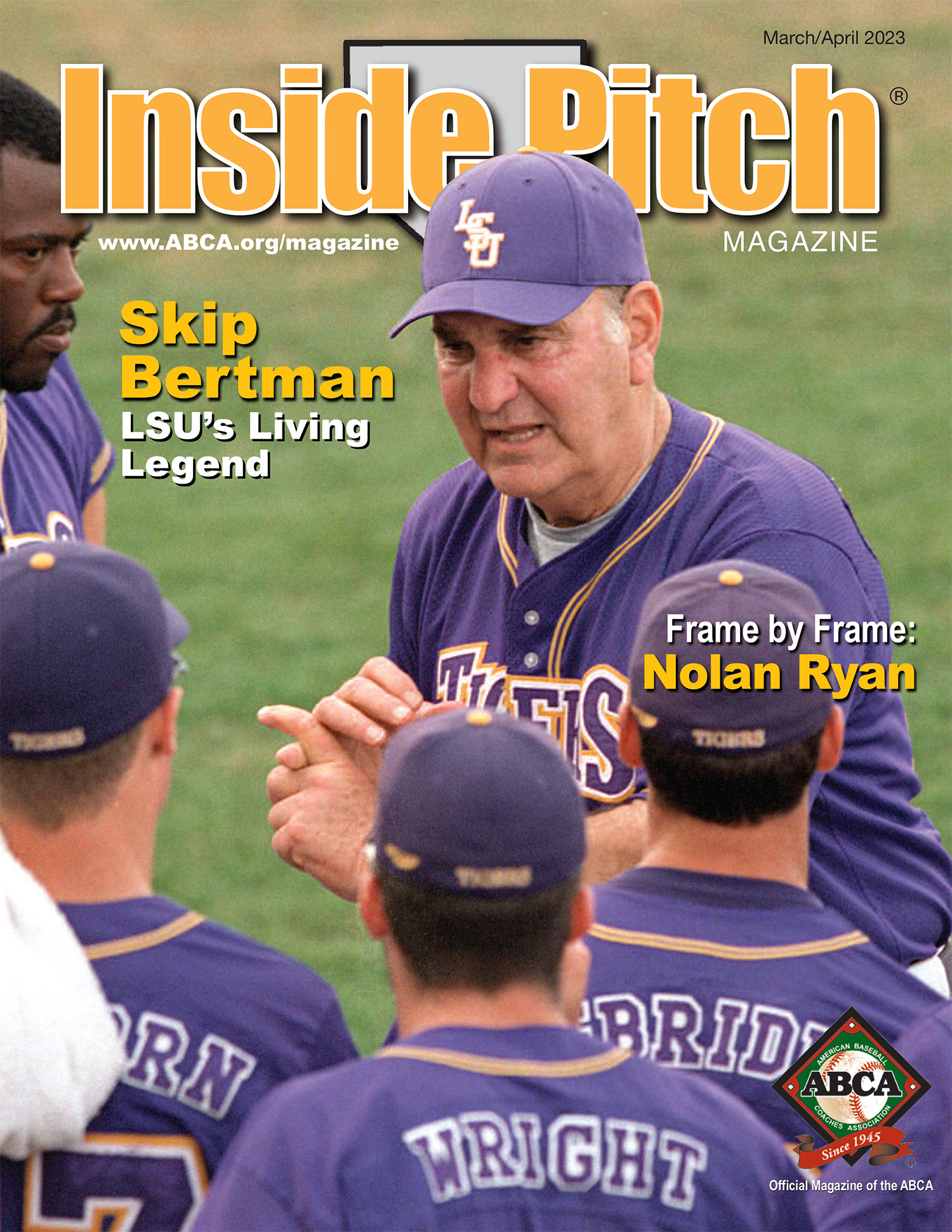

Skip Bertman is quite literally a living legend. A man whose name is adorned at one of college baseball’s premier ballparks—Skip Bertman Field at LSU’s Alex Box Stadium—also has his likeness in the form of an eight-foot, 3,500-pound bronze statue at the center of LSU’s Legacy Plaza. The mark Bertman continues to leave as a former college baseball coach and athletic director reverberates across the country in the form of coaching trees, philosophies, and in simple gestures of honesty, humility and character from our leaders.

“Everything Matters in Baseball” is a 248-page book published in 2022 all about Skip—his work ethic, personal traits, and overall contributions to the game of baseball and the game of life. “Everything Matters” includes chapters on each of Bertman’s five National Championships, secrets to training great pitchers, how to embrace the power of positive thinking and more. It is based on personal observations by author Glenn Guilbeau along with interviews with former players, colleagues and family members.

Inside Pitch: Skip, it’s an honor. You’re one of the all-time greats in sports when it comes to being a lifelong learner and having a detailed plan. How long did it take for you to develop your system?

Skip Bertman: I’ll be honest and I don’t want to sound boastful, but I really never did anything but coach. I wanted to be a baseball coach when I was 13, and I started to coach when I was 14 with the local youth league. I had exceptional mentors and I was very, very lucky. Max Sapper was a former pro player who worked at the recreation department where I grew up. He wasn’t like other people, he was really coaching. He didn't care if the balls were white or whether your bat was the perfect fit for you or not, he wanted us to be well coached, to do things right. It was a different time of course, but I learned so much and I really enjoyed the heck out of being around Max.

Also, there was W.D. Cole, a high school coach who realized that I wanted to know everything there was to know about baseball. Coach Cole worked so hard to get whatever books, magazine articles and other resources he could find, including people in college or professional ball. I was a shameless brain-picker—I just went for it. So I had a lot of information when I went to play ball, and even had some draft offers out of high school, but I wanted to go to college because I wanted to be a coach. So I went to the University of Miami. By the time I was done, I was pretty much coaching our team. The coach at the time was a former football player—great guy— but one day he just said, “You do it, Skip.” Now today, of course it’s just not like that. But it worked out great for me!

IP: Let’s talk about your book. I love the title of “Everything Matters.” Is that concept more about taking all of the intricacies andwrapping it up in a simple, digestible fashion for your players? Or is it about diving into the granular details of coaching so we can better understand what we’re doing?

SB: That’s a great question. I just wanted to capture what I did as a coach and how I did it, so it'll be good for other coaches down the line. Certainly you can play the game and have a good program without doing all the things that I did, but I think the way we thought about things was maybe a little deeper than how others did it.

You see, I don’t buy the term “overcoaching.” I’m not sure what that really is. Now I don’t want to give so much information that the boys are confused, but it’s my job to ensure that everyone understands Plan A before we move on to Plan B and of course, Plan C. I liked the teaching that came with coaching; kids would come in that weren't well coached by my standards, and I knew I had three, four or even five years to make sure that they could play and help us win and get to Omaha.

IP: How would you have handled NIL?

SB: NIL is really something that’s new and very, very scary for a coach. We really don’t know how much the coach will have to be involved, how much people are going to use the transfer portal versus recruiting high school or JUCO players. It’s made us all into “cheaters.” We're okay to cheat now, as it seems like there are no rules anymore. And that’s what’s scary.

We had plenty of transfers when I was coaching, and we never had a problem with it, but of course there was no money involved. If they can find a better place to play or I’ve got three good catchers that can all play, I guess one of them probably should transfer. And I like that for the players. But the NIL, whoa, I don’t know.

IP: Is technology helping or hurting the game?

SB: Well, it’s making a tremendous impact one way or another, obviously. I watch our bullpens here at LSU with the TVs and the tech going. It’ll always be strange for me to watch the pitcher throw a pitch and then both the pitching coach and the pitcher would turn around and look at the TV. I kind of chuckle with all of that because when it comes to pitching, it’s all about reading the swings of the opposing batter. We have all the information everyone else does now about whether hitters are swinging at 3-2 breaking balls, taking every first pitch, things like that. The technology is fine by me, but any successful team still has to do the basic stuff.

I used to work with all of my pitchers about 40 times a year in the bullpen, talking with them, giving them what-ifs and how-tos.

IP: Is it an advantage or a disadvantage to be a head coach who also runs the pitching staff?

SB: I’ve always felt—very strongly—that it is an advantage. Calling pitches is a tremendous responsibility, and being able to do it as a head coach is an advantage because I knew whether or not I was going to make a pitching change in advance of all the pitching calls that I made. I also knew the most about the pitchers, having worked with them in the bullpen. I had practiced all the pickoff plays and other elements of pitching: how to correct a pitch, how to fix the next pitch so you don’t walk two in a row or even more. But whomever is handling the pitching has enormous status in the outcome of all ball games.

I tried to watch a lot of video, collect any pitching charts I could trade or find. I would know based on the video, the charts and the first couple at-bats what he was trying to do. And I was a fastball-down-the-middle kind of guy. When the kid was hitting .167 or .204, go right after the guy. You don’t need your knuckle-Vulcan death grip pitch for this one, just challenge the guy.

IP: Could your pitchers shake you off?

SB: Yes. I want you to be committed as you can be to each pitch. I don’t want you to throw a curveball away if you really want a fastball in. If you're going to allow the guy to shake you off as a coach, then you can’t ever criticize it. Your players can’t have conviction and doubt at the same time.

IP: How much of the scouting report did you want your players to have access to?

SB: Just what they needed individually. I wasn’t fine point coaching the opposition, for instance. If we knew what the pitcher threw in certain counts, we would focus on that, especially if it was at a rate of 95 percent or something like that.

That question makes me think of one season when we opened up with Kansas. I would talk to a booster group early in the year, and they’re asking “What do you know about Kansas, coach?” Like it was a football game, where you really do need to know everything about what kind of offense or defense your opponent runs. I’d say to them, “it’s not like that…” I was very patient with basically a non-response and they loved it. I think that’s how I drew a lot of fans into our booster group, which was a very important group. They understood what I was doing, even if they didn’t know as much baseball as I did. I figured if I could explain it to my boosters in a way they could understand, I could do the same for my players.

IP: Is the public-facing part of the job something you had to get used to?

SB: I thought I was a hot-shot at age 36, which was when I went to the University of Miami for eight years. But Ron Fraser taught me so much about reading people, handling boosters, speaking in public, so when I came here to LSU, I was very well prepared. I had a bevy of things to tell the people, including jokes that hadn’t reached Baton Rouge yet; I knew I had a few years to tell the jokes I’d heard in Miami because word doesn’t travel as fast to Louisiana!

I did have to make an effort to be patient, to be pleasant, to be mature. I wasn’t really any of those things before I worked with Ron. And those are great things to be in your life as well. Mothers loved it because they knew that I wanted the kids to graduate, get a good education and be good husbands and fathers. I would tell the kids to call their parents, don’t ask for money, tell them you're doing great and you love them. Because that’s all they want, is for you to be happy.

But ultimately I never had a problem with parents, fans, boosters, any outsiders, really. Most of them are decent people whether they knew how to hit a curveball or not, and I always told myself that every parent, fan, booster, outsider was helping the program in their own unique way.

IP: How much impact did the parents have in your recruiting process?

SB: One of the simple things I looked for was whether the parents joined the kid on the visit. That was a big thing for me. That tells you that there’s support in the home, there’s some teamwork there because there may be another child, a daughter or another son, but they’re helping this one at this time. Any parent, of course, knows what that’s about.

And I watched the kid. If he looked in his shoes when I was talking, I probably would let him go, even though he might have been a good player. I had certain standards. But if I liked the kid and his parents, when I met him on Sunday and they visited, I’d just go with their coaches’ recommendation on how good the kid was. No way you can get away with that anymore, and I don’t want to sound pompous, but my philosophy was that I could build this kid into the program.

They’d say “Hey Skip, we just got a guy from Elmer, New Jersey.”

“What position is he playing?” I’d ask. “I don’t know,” they’d reply, “maybe an infielder. Played a little hockey.”

Next thing you know, the kid would come down and he was a good athlete and after a year or two he was a real good player. (Elmer, N.J. native Tookie Johnson played in 256 games over his four-year LSU career, batting .309 and striking out only 70 times in 900 at-bats).

I learned from Ron—again—that you have to be patient. You can’t expect every guy to come in and be a superstar, but you can expect every guy to give 100 percent, buy into the program, and be supportive of their teammates. From there I could teach him, work with him, help him, get him bigger, stronger, faster, smarter. If he can’t play in his first year, I’ll get him there in that second year. And if not year two, year three. I won't give up on anybody, even if it takes them four or five years. If you get them playing their fifth year when they’re 22, 23 years old, they become men amongst boys.

It works just like it does in football when you’re bigger, stronger, and older, or even in basketball. Baseball is similar. We can have guys play as freshmen as they do in football and basketball, but most of them have to be built: taught, trained, and worked into the system.