According to Fangraphs, non-pitchers in Major League Baseball from 2000-2004 had 5,219 sacrifice hits (bunts). From 2013-2017, the number of non-pitcher sacrifice hits dropped to 3,333, a 36% decrease. For anyone who follows baseball, that decrease is probably not a surprise; multiple analyses of the current Major League run scoring environment have demonstrated that giving up outs to advance base runners can negatively affect a team’s ability to score as many runs as possible (See chapter 9 in the book Playing the Percentages in Baseball).

But what about at the high school level? Do high school offenses receive more benefit (i.e. have the chance to score more runs) from sacrifice bunting? An examination of high school Run Expectancy can begin to lead to answer.

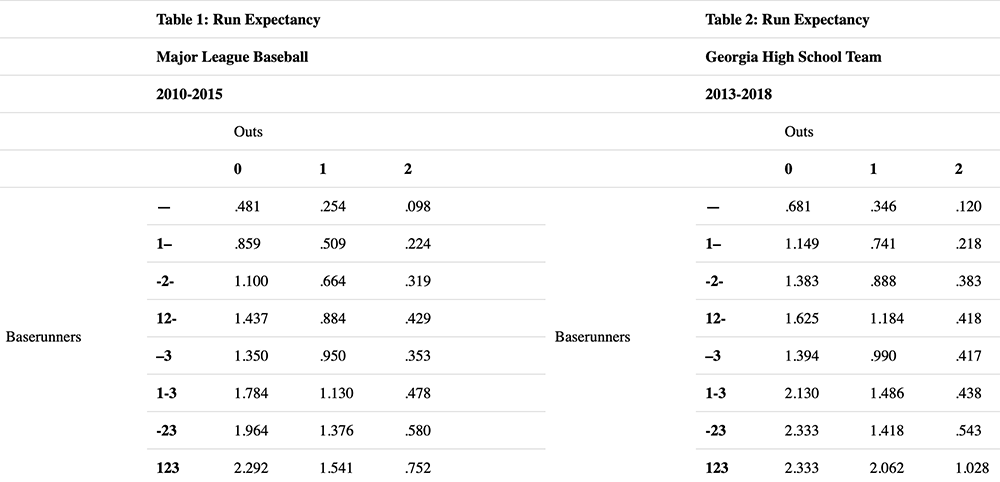

Run Expectancy is simply a measure of how many runs a team can expect to score (or has scored on average) each inning. Table 1 and Table 2 are Run Expectancy tables that break an inning down into each of the 24 base/out states and show how many runs a team or league scores from each specific state until the end of the inning. Table 1 shows the Run Expectancy for Major League Baseball from 2010-2015 (taken from Tom Tango’s website

www.tangotiger.net), while Table 2 represents one Georgia high school team’s run expectancy from 2013-2018 (this data was collected by the author).

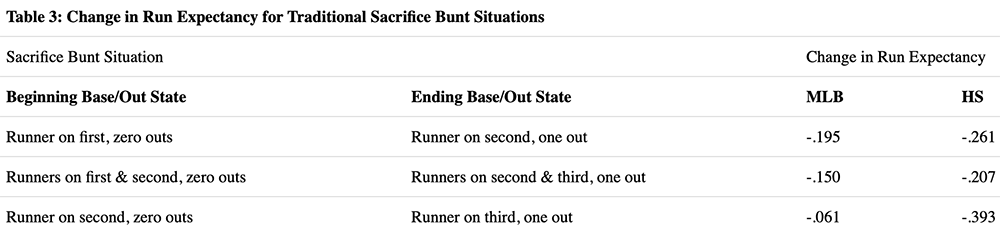

On average, when a Major League team gets a runner on first base with zero outs, it scores .859 runs until the end of the inning. When a team gets a runner on second base with one out (the typical result of a successful sacrifice hit), it scores .664 runs until the end of the inning. That is a loss of .195 runs.

The high school team loses more runs in that scenario. According to Table 2, with a runner on first and zero outs, the high school team scores 1.149 runs until the end of the inning. A runner on second and one out nets the team .888 runs until the end of the inning, which is a loss of .261 runs. Table 3 presents more common bunting situations and the change in Run Expectancy for both MLB and High School. In every scenario, the high school team loses more runs than the Major League team.

Taken in broad strokes, the data indicate that sacrifice bunting at the high school level can be more detrimental to scoring as many runs as possible in an inning when compared to MLB averages. That does not mean that sacrifice bunting is always poor strategy, but instead a tool that should be used carefully in advantageous scenarios. As the authors of Playing the Percentages in Baseball discuss, such advantageous scenarios can include (but are not necessarily limited to) when weaker hitters are up to bat or in certain early game situations. Sacrifice bunting scenarios are also likely in late inning, low scoring games and could also be used as a way to surprise a defense, or to capitalize on subpar defenders on the mound or the corners of the infield.

Of course, not all plate appearances that involve a sacrifice attempt result in a sacrifice hit, meaning the lead runner is successfully advanced and the batter is put out. Other positive offensive outcomes- such as the batter not being put out or the lead runner advancing multiple bases- do occur, whether via the result of a well-placed bunt, defensive mistake, or something else. On the flipside, negative outcomes such as the lead runner being put out or the batter failing to get the bunt down also transpire. Whether positive or negative, these outcomes do affect the run value of a sacrifice attempt and could make the sacrifice attempt more valuable than the actual sacrifice bunt.

Unfortunately, tracking instances of plate appearances that contain a sacrifice attempt but not a sacrifice hit can be difficult at the high school level, as most scorekeepers and scoring software only track when a ball is bunted in fair territory. The authors of Playing the Percentages in Baseball address this situation at the Major League level and determine that while the sacrifice attempt does have a markedly higher run expectancy than the sacrifice bunt, the sacrifice attempt’s run expectancy is still lower than allowing a hitter to swing away. Until better data is presented at the high school level, the safest assumption is that sacrifice attempts would act similarly at the high school level. Besides, few coaches are going to call for a sacrifice bunt hoping the attempt results in something better than an advanced runner and an out. The reason the coach calls for the sacrifice bunt is because they are willing to give up an out.

As such, for a high school offense that is trying to score as many runs as possible in an inning, sacrifice bunting should be used sparingly, and probably never when the top hitters are up to bat. The math is plain: giving up outs to advance baserunners diminishes the number of runs a high school offense can expect to score until the end of the inning, even more drastically than it does at the Major League level. Simply put, the slower an offense can deplete its outs, the greater its run scoring potential will be. Outs are a limited resource, don’t give them away!