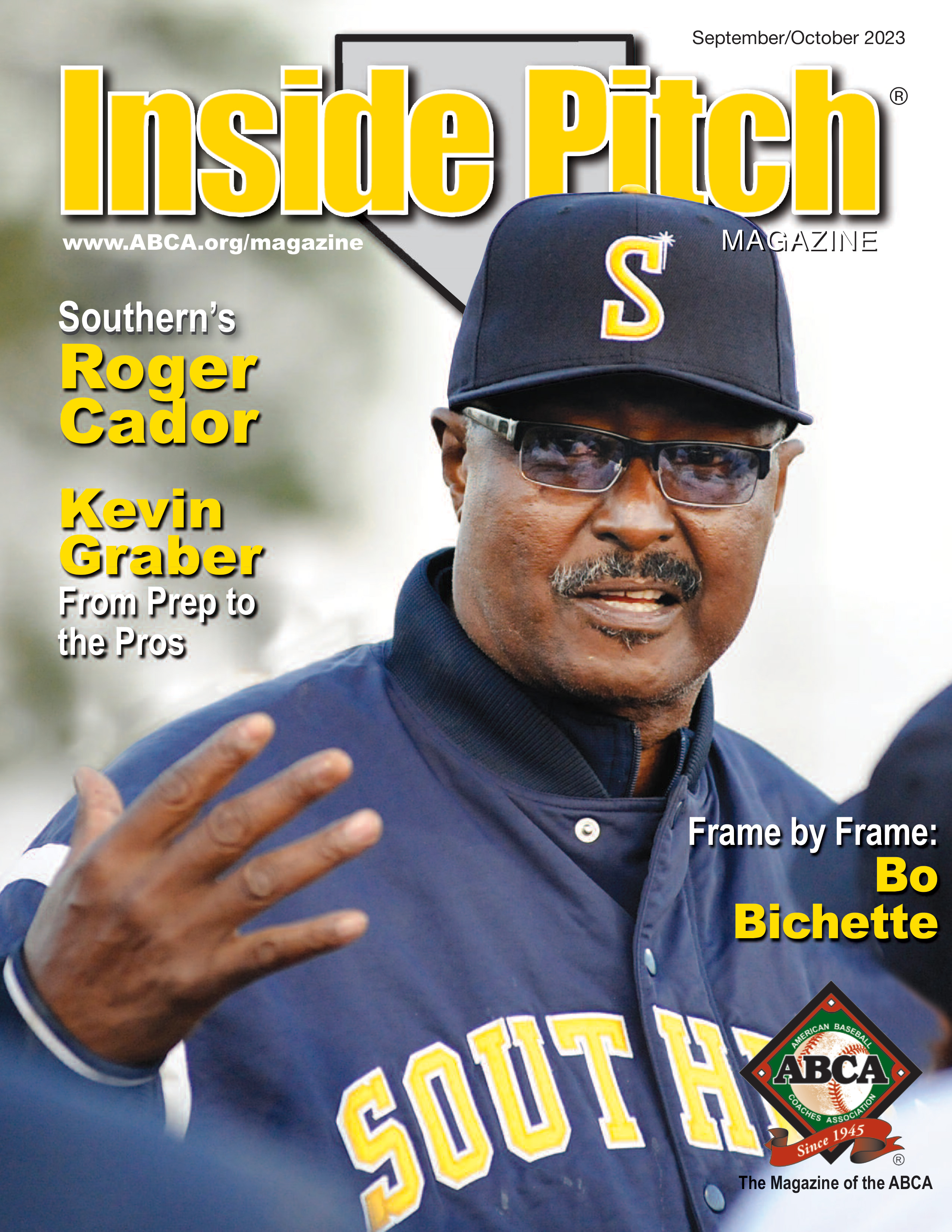

Roger Cador knows a thing or two about “impact.” The winningest head coach in the history of Southern University made a lasting impression on the field, compiling a 913-597-1 record over 33 seasons with the Jaguars. His 1987 club became the first HBCU (Historically Black Colleges and Universities) team to win an NCAA Division I tournament game in 1987, a 2-1 triumph over Cal State Fullerton.

Cador is a member of the Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame, the American Baseball Coaches Association Hall of Fame, the Southwestern Athletic Conference Hall of Fame, the Southern University Hall of Fame and the College Baseball Hall of Fame. Baton Rouge mayor Sharon Weston Broome declared Friday, February 3, 2023 as Coach Roger Cador Day in Baton Rouge.

Cador also has an eye for impact players, having—in his own words—sold “the hope and the dream” to a multitude of all-conference players, 62 MLB draft picks and even 2003 Golden Spikes winner Rickie Weeks. More importantly, he graduated his players at around an 80 percent clip at Southern.

“I told them—and mainly their mothers—that I would be a father figure, instill discipline, do whatever we could to get them a degree,” said Cador. “We didn't have a baseball field, a locker room, equipment, nothing. We found a patch of grass on campus and that’s where we practiced. We’d take ground balls in that spot and we hit, that’s all we did.”

Impact is not always instant.

“I got on the phone and I made a call to Dusty Baker, who was with the Braves at the time,” recalls Cador. “We met in Atlanta and he gave us a bunch of equipment that I U-Hauled back to Baton Rouge. From there, we got some other things falling into place, and I had great kids who understood how it was gonna be.”

Cador has continued to blaze new trails for minorities in baseball beyond his coaching career. He’s been called the “heart and soul” of the Andre Dawson Classic (formerly the Urban Invitational), who came up with the idea along with the late Jimmie Lee Solomon, and Darrell Miller, MLB Vice President of Youth and Facility Development.

But most anyone who knows the man will tell you that Roger Cador’s impact beyond the diamond reaches much further than the pristine winning percentage, the milestone victories, and the Rolodex of diamonds in the rough he’s found. In 2013, Cador was named to the Major League Baseball Diversity Committee by Commissioner Bud Selig, and he hit the ground running ever since.

“I got involved before I retired from coaching. That gave me a different perspective on minorities in baseball from the highest of levels. I was in the room with club presidents, general managers, and owners. We were coming up with a blueprint for what we wanted to see happen as we tried to grow the amount of African Americans in baseball. We had been on a 30-some year stretch where we just did a poor job with that. These black kids were all playing other sports, and their kids and grandkids grew up watching them, and there you go. We had to reverse course and try to re-recruit them, basically.”

“Back in the 1940s, ’50s and ’60s, when the supply of players was plentiful, there was not a great demand, simply because baseball was just starting to integrate. So when football and basketball gained popularity, baseball had fully integrated, but the supply was no longer. Now we have a healthier, growing demand for African-American players, so we are trying to reinforce the supply through the Andre Dawson Classic, the Hank Aaron Invitational, the Breakthrough Series, the Swingman Classic.”

Cador spoke to Inside Pitch from an office at the Vero Beach complex, training site for the Hank Aaron Invitational, a youth-oriented, on-field diversity initiative that aims to get high school-age players with diverse backgrounds to the next levels of the game. Approximately 250 U.S. players aged 13-18 earned the opportunity to receive elite-level training from former Major League players and coaches that have included Jerry Manuel, Ken Griffey Jr., Dave Winfield, Tom “Flash” Gordon, Eric Davis, Marquis Grissom, Delino DeShields and Cador himself. Ultimately, 44 (Aaron’s old jersey number) players are chosen to compete in a special showcase game at Truist Park, home of the Atlanta Braves.

“It's a wonderful experience for them,” said Cador. “Funding comes from the MLB-MLBPA’s Youth Development Foundation, so there is no cost for the kids, a majority of whom would never be able to afford it. And there is a bunch of former big leaguers hanging around instructing. But these events are not vacations by any stretch of the imagination. We get to the park early and we’re up there until three or four o’clock. It’s instruction, training, a break for lunch, and game play, just like Rookie ball. The goal is to prepare these kids to go to HBCUs and other colleges.”

Cador was also a key cog when it came to the HBCU Swingman Classic, which debuted in Seattle during the All-Star break in 2023.

“That one certainly didn’t happen overnight, as you might imagine. Tony Reagins, Del Matthews and myself had been working for years to try and put together an HBCU All-Star game. We were planning on doing it here in Vero Beach until [Ken Griffey] Junior came along and asked about bringing it to the “house he built” in Seattle. Of course that made complete sense, and it really helped us get the right people on board from a financial standpoint, because it was an expensive undertaking when you’re talking about getting people all the way across the country from the HBCU footprint, which is mostly in the southeastern United States and up and down the east coast.

“I thought it came off wonderfully. We developed a committee to make sure we saw all the kids from the HBCU schools, which was a requirement. I got to see a lot of them myself here in Baton Rouge at the Andre Dawson Classic. I had a bird’s eye view of the talent, and we utilized some professional scouts. Everything really worked out well.”

Cador’s watchful eye has also noticed the changes that college baseball has undergone in recent years. “The transfer portal definitely makes it interesting for the HBCUs and every other mid-major. The rich are getting richer, but that’s how it always is, and wherever there are challenges, that means there have to be opportunities as well. After all, there’s only one team that’s going to be left standing at the end with a national title. Everyone else loses their last game or wasn’t good enough to make the postseason anyway.”

When asked how he would handle it if he were still running the show, Cador said it’s all about the people. “You’ve got to work the people. If you’re doing your job, you’re going to lose quality players sooner than you think, to the draft or to the portal now. And maybe you’re not as good as a result, but you can still be a good program if you’re working tirelessly to find other players. You think I would’ve kept a guy like Rickie Weeks nowadays? Maybe, actually, because I kept him when he was here after all [Weeks played at Southern University from 2001-2003, when he was the second overall pick in the draft]. When I sent Rickie to Team USA, there were some bigger schools that tried to steal him, but he wouldn’t budge. He was loyal to me, to Southern, and to his teammates. And he had a great mother who made him listen when she said I was the coach for him!”

Cador had some other tricks up his sleeve when it came to recruiting. Since his assistant coaches did not make a substantial salary, he was able to place his coaches in pro scouting jobs in and around the area. “I had seven former assistants that were all helping me as pro scouts at one time. I was sending them out like they were still working for me! It was a great system, I kept getting my assistants better jobs and they kept sending me players. That’s how I found Rickie Weeks. He didn’t do anything the day I saw him. Didn’t get a ball out of the infield, but I was sold on him before he did any of that, because I got to the park early and guess who was the first player there? His preparation, his physical tools, the way the ball came off his bat, we were in business from the jump, even though he didn’t get any hits that day.”

Cador also admitted that his ways would have to change in some areas, thanks to the facilities improvements across the landscape of mid-major college baseball. “I’m not sure that coaches today would want to do it how I did, to be honest. We practiced for about an hour a day, I wouldn’t let any of my kids miss class, so we never had a full team. We did very basic things and never tried to be sophisticated. My kids were “babies” from a baseball standpoint when they got to me, good athletes who just needed help with the fundamentals. And you can’t give a baby solid food, right?”

“I had to make sure that we could execute what we needed to win games. And that’s the basics. Now, the players that could handle more, I would give them more, but that’s how I did it. I see a lot of coaches now want to do things one way, line all their guys up the same way when they throw, hit the same rounds of BP. That just wasn’t me.”

In addition to being himself, Cador allowed his players, and therefore his teams, to be themselves as well. “I wanted to get feedback from players. They needed to know that they were dealing with a coach that wasn’t ever going to know it all. That really empowers a team, when the group knows that they have the power to make suggestions and adjustments that will make them better. Most importantly I made sure my players knew I cared about them.”

“It's hard to change people, we’re all creatures of habit, right? So I would allow my players to be themselves, and would add a little refinement in some areas. A guy who is aggressive, who likes to talk a lot might be problematic at times, but he’s not going to be a good player if you prevent him from being aggressive or talking! That’s not who he is.”

Toughness, persistence and consistency were staples in Cador’s programs, and they were implemented from the top down: in 33 years, he never kicked anyone off his teams. “How could I put that kid back on the street? What was the result going to be? We may be the only hope he’s got,” Cador said. “So we made sure he felt that discipline by making him watch practice or games without being able to participate, which is tough, but they had to stick it out. Before you know it, these kids are going to have families of their own, and they need to be able to stick it out, just like they stick it out with me. I’ve heard it several times and I still do today, guys come back around or call me and say “Thanks for keeping me around. You saved my life.’”

Cador, who had a unique upbringing of his own, can appreciate the opportunities to use athletics as a means for educational opportunities, and vice versa. At age 14, Cador had to convince his father, a sharecropper, that he would have greater opportunities if he went to school, and would eventually graduate from Rosenwald High in 1969, ultimately attending Southern on a basketball scholarship, four years after he had actually been cut from the Rosenwald program.

“And we’re doing a better job with this thing,” Cador says of minorities in baseball. “We’ve seen kids from these specific events pop up on draft boards and get opportunities at the next level, whether that’s professionally or in college ball. And those numbers will keep growing. I'm so happy that I'm able to have the life I’ve had, with all the years I coached and now helping to sell baseball to African Americans, trying to put them at the forefront. It really feels like I’m a part of it and that I’m making a contribution.”

For more information:

• mlb.com/hank-aaron-invitational

• mlb.com/youth-baseball-softball/andre-dawson-classic

• mlb.com/all-star/mlb-develops-days/hbcu-swingman-classic

• mlb.com/breakthrough-series